Chapter - 1

Chapter - 2

Chapter - 3

Adjacent Essay

Namaste Friends,

So many of you are new here, and I want to warmly welcome you to Berkana as we are now in 2026. If you wish to understand my work more fully, I invite you to spend time with the archive. I am not a writer who fits neatly into a single niche, and my work resists easy categorisation. For this reason, I remain deeply grateful to readers who are willing to listen to a voice that is neither prominent nor mainstream. My work tends to linger within the layered understructures of society, with processes that take time to shift and re-form, like roots working quietly beneath the soil.

The debauchery of the world as we know it is such that when the façade of performance finally falls away, it is often the most innocent among us who are left to speak, with an urgency that also asks much of its listeners. Those who obstruct the possibility of fairness, rhetorically and materially, will never be the ones to ask the necessary questions of systemic injustice. This essay was originally meant to be the closing paragraph of the second piece in my Meghalaya series. But as I began threading its nuances, it became evident that to confine it to a single paragraph would be an act of erasure in itself. I therefore set out to write this essay as an adjacent, necessary continuation of the series.

As it goes with recorded and popular history, the interest of the masses often resides in the shallow end of the ethnographic map that reads neatly along a chronological line, consumed largely as entertainment or curiosity. I am not suggesting there is something inherently evil about history as entertainment, however chained or reduced it may be in its Enlightenment-era costumes. But for those of us who honour lived experience and ancestral memory, history must be more than a parade of pretentious facts. And for those simply fatigued by the oversaturated literary markets of late-stage capitalism, history must serve a purpose beyond aesthetic consumption.

In its deepest service, history is a tool of forewarning, a means of interrupting futures that threaten to repeat themselves when the past is treated as final. The past is not inert; it is a ghost, a ghoul, held within the edifice of time, carrying as much potential for life as anything in the present. History, therefore, is more than recorded fact. It is a cauldron of living memory, a mirror of what has been, and a mnemonic of desire—all consolidated into a single narrative force. It offers us insight into a repertoire of possible unfoldings when systems meet, even as dominant recordings of fact insist on narrating only one sanctioned path. Contrary to popular belief, history is cyclical. This is precisely the idea that public historians, those who find comfort in linear timelines without risking the ethical consequences of interrogation, remain deeply averse to. This essay stands as a challenge to their “actual facts and statistics” model of history.

Tending the Colonial Wounds

Much of the written history (by the British) of the Khasis has been redacted in order to erase the pre-recorded oral and ancestral folklores. This hardly comes as a surprise knowing there exists a whole field of study dedicated to decolonisation of academia1. But sometimes lived experiences are charged with emotional and cultural wounds that academia is inept to handle with the compassion it demands.

In the margins of these forgotten tales of the Khasi freedom struggle for Independence hides the story of Ka Phan Nonglait. She is a hero unlike any other since she fought the battle both spiritually and socially, ensuing the first Anglo-Khasi war. Her story has been understated in the colonial records, but since Khasi tradition has always relied on oral traditions of storytelling, the epic of her heroism soon caught on like fire on a haystack, and it now occupies a prominent place in Khasi folk memory. The first recorded history of the Nonglait clan is attributed to the Khasi writer T. Daniel Stone Lyngdoh Nonglait in his seminal work Ka Jait Nonglait: Ka Thymmei bad ki Dienjat.

Ka Phan Nonglait was born in 1799 in Nongrmai, into the matrilineal Khasi world as the youngest daughter who carried responsibility for land, lineage, and continuity of her family. When the East India Company started its devious plan of building a passage through Nongkhlaw to control the Meghalaya-Assam plains, the intrusion unsettled more than just the terrain. The reverence, ritual, and the lived relationship between people and nature that the Khasis celebrated were massively disrupted by this colonial activity. British occupation brought everyday humiliations that travelled quickly through villages, and nature’s subjugation directly registered itself in women’s bodies. Abduction and rape of women and girls were of daily occurrence, and most of those cases went unrecorded. Ka Phan Nonglait’s molestation in 1829 crystallised what many already sensed: colonial presence was inseparable from violence. She transmuted the grief of bodily violation into challenging the power structures and status quo of her time. She allied with the local women and mobilised a movement, feeding popular resistance that strengthened the resolve of leaders like Tirot Sing.

Disguised as a forager, she approached resting British soldiers, shared spiked liquor, waited for their vigilance to dissolve, and disarmed them, casting their weapons into the gorge below before signalling nearby Khasi warriors to arrest them. The act reflected a resistance shaped by patience and eco-wisdom rather than mathematical precision or military force. She lived beyond the war’s fiercest years and died in 1850, leaving little trace in colonial records. Khasi memory holds her in transparent reverence near one of the waterfalls that bears her name. Through all these centuries, what endured reflects the relevance of eco-consciousness of the Khasis. Ka Phan Nonglait is bigger than the body that she inhabited. Her courage resonates through the gorges and valleys and is now embodied by the West Khasi Hills’ landscape itself. Her imprint on land and memory reminds us that resistance is a luminous and quiet process moving at the pace of forests rather than empires, and lasts twice as long.

Nature as a Portal to Memory and a Realm of Defiance to Religion

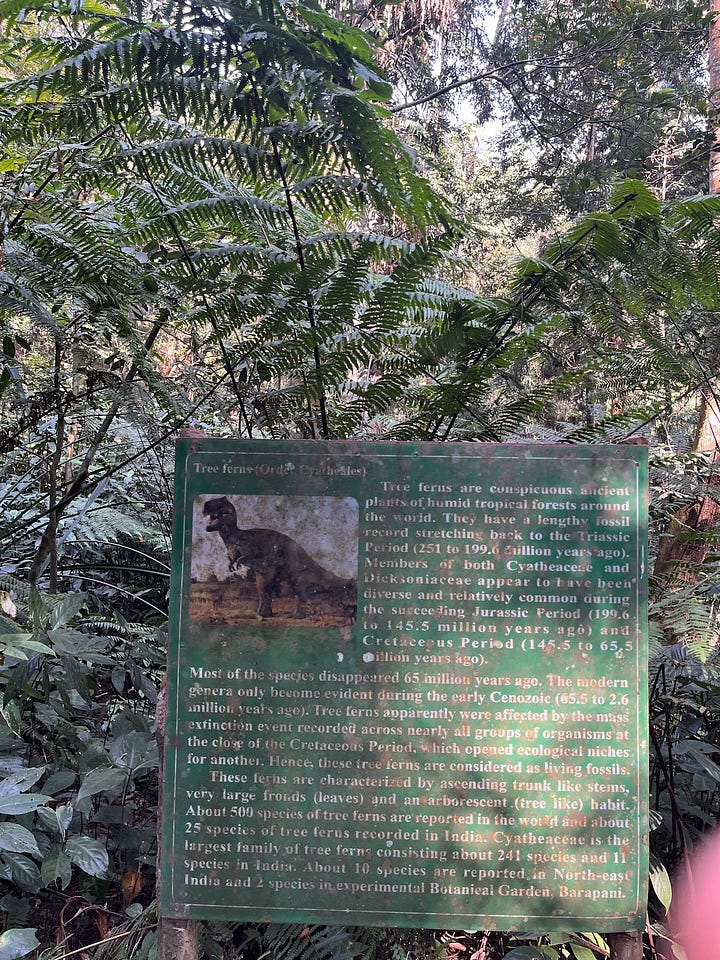

It was by the abruptness of luck on the second day of our one-week stay in Shillong that we discovered the experimental botanical garden in the province of Umiam. It was slightly further from the heart of the city, and we reached there slightly fatigued after wandering through the Don Bosco Museum’s archives that reeked of missionary propaganda. The exhalation of a fern nursery in the garden was indeed a safe place to reflect, away from the church masquerading as a museum. Trees have an inherent relationship with place and its memory, and hence are a better vessel and interpreter of history. I wanted to learn from the Earth, her story.

Although not open to outsiders, the day we arrived two botanists were studying inside the campus nurseries while making meticulous notes of their observations of the shape, texture, and condition of the leaves. The fern nursery sits at the heart of the centre, which aims at reviving some Cyatheaceae species that have been around since the Jurassic Period and have been going extinct due to modernisation. Suspecting that our unannounced arrival must have annoyed them, AK quickly resorted to his industrious explanation of my writing projects and interest in learning about nature. Curiously, they were not the least bit inconvenienced by us. They, rather enthusiastically, agreed to give us a tour.

The scholars went into great detail while walking us through the nurseries, bamboo groves, unkempt overgrowth of gigantic ferns, and narrow ravines with streams seamlessly flowing through them. For some reason unbeknownst to me, I listened to the scholars disembodied. I was, as if, by a stir of presence, pulled into ruminating about the witnesses that nature becomes in suffering of other beings. While learning about the medicinal nature of the flora in the garden, my awareness kept launching itself into bigger orbits of existence. I wondered about the stories, intimate ones, painful ones, and the need for them to belong in the commons, like the medicinal plants, so that they can create a universal access to acceptance and healing.

Exhuming the Graves of Memories

I had known Ophelia for some years before I interviewed her. When I requested to interview her on her Khasi roots, she graciously agreed. She appeared on the video call as she has always been — bright-eyed with her booming uninhibited belly laughter. Ophelia has a powerful voice and a pair of deep-set, fierce black eyes that commanded attention in every room she entered. She is, as Dr. Maya Angelou puts it, a phenomenal woman. She is an artist of tremendous calibre, but she held a day job, like most of us who have bills to pay. She met me halfway in the conversation, reeling in contempt for the extractive nature of the corporate world. She belonged to the legendary Khynriam Kur or clan2, as she announced with an air of unrehearsed elegance. I somehow hid my adoration for her disarming grace and intelligence, lest she get distracted by flattery.

I began by conversing nonchalantly, “Tell me about things that you are proud of in Khasi traditions and others that you are not.” She reflected for two minutes before saying, “Well Swarna, I can tell you a few things I am proud of, and a ton of things I am not. But only if you are ready to hear it.” I knew then the conversation was going in a direction that would challenge both my objective admiration and high regard for the Khasi society. But I was prepared for the truth, so I insisted that she continue.

She began by stating the importance of a strong communal sense of belonging and a safe space to grieve within the Khasi value system. She, with obvious pragmatism, declared the matrilineal system as the only fair system of tracing lineage, given that the mother carries the child in her aching and changing body for nine laboriously long months. As per Ophelia, bodies are the vessel to connect with land and family — two of the most important facets of Khasi life — so bodies are of utmost significance to societal life.

Both birth and death, in all their complexities, are shared equally within the family and the clan. Pregnancy, Ophelia emphasizes, is never treated as an individual burden. The mother-to-be is always well cared for and highly regarded by the community. Birth is a threshold and hence a special occasion. She attested to similar reverence for death in her society. When someone dies, the body is not rushed away to be buried. Since Meghalaya has difficult terrain and in the past people used to arrive on foot, the elders have decidedly made it a tradition to keep the body for three days so that people can arrive at their pace, sit together, and grieve without haste. Death, she said, has a way of reuniting families who have otherwise drifted apart.

When the topic of matrilineality arose, she handled it with boredom that can only be fostered by familiarity. Everything that seems so empowering to us, for Ophelia, was just how things were. The youngest daughter becomes the anchor of the household. Property passes through her. The man who marries the youngest daughter goes to live in his wife’s home, and children carry their mother’s name.

I floated around it slightly before steering the conversation a little towards her personal experiences. Here is where the narrative thickens further. Suddenly her eyes darkened, almost in grief, and the air stiffened within the digital space between us. I told her it is okay not to share if she does not wish to. But she took a deep breath and insisted that she should go on since it was important to her to tell it right. She leaned back slightly in her armchair and smiled that illuminating smile of hers before going into painful details of her past.

Ophelia, like several other Khasis, was born in a Christian household. The shift from animistic to Christian faith happened around the arrival of missionaries during the colonial administration. Her mother, who is a staunch and orthodox Christian, had probably adopted the new faith perhaps because one of their ancestresses was convinced to leap into it to find a sense of belonging within a larger organized religion. This choice would not have been a complete disaster had Ophelia not been a fiercely independent person and had the church not been the sole reason she now is less fond of her hometown.

Although she carries deep admiration for her mother, Ophelia bluntly stated her qualms with her mother’s orthodoxy. Ophelia’s matrilineal Khasi roots, which reveres the feminine, are in direct clash with the controlling ways of the church. At some point, she was sexually violated, which left her with deep psychological abandonment. When she chose to put her faith in the priest by confessing about this, he betrayed her by raking her personal life in public circles. The treachery made her vulnerable within her close-knit community. In time, rumour spread of her pregnancy, and she was eventually met with many painful judgments. The whole experience made her break truce with religion, and she hardened herself in retaliation. Although when I look at Ophelia, I can never imagine the word broken, I knew in my heart that some part of her still wants the story to be told and heard in the right way, so its haunting might cease once and for all.

The consistent lack of kindness for female agency reflected within conservative Christian values is deeply in disagreement with the women-first, mother-first Khasi matrilineality. These two traditions do not agree on the degree of liberation that a woman deserves. It creates psychological schisms in an individual’s memory, one who had to walk the tightrope of weirdly constrained definitions of freedom, where one is powerful enough to consult an entire army of ancestors and carry their legacy, and yet not free to do as they please with their own bodies.

Bodies and Land as Archives of Past

These anecdotes once more justify our conviction that colonial emphasis on wealth, power, and control had been the earliest foundation stone of madness that continues to engulf the world whole in its greedy flames. It is the very reason the world spirals into a perpetual state of brokenness and despair. It is going to take more than just a bunch of wellness programs, yoga retreats, and self-help books to stop the wheel from spinning in the wrong direction. What is required instead is truth, courage, and a willingness to confront systems that continue to thrive on erasure and control.

The stories of these two women, separated by nearly two centuries, speak to the same unbroken thread of feminine resistance. What strikes me most is the way memory itself becomes refusal to degradation. The wounds inflicted by colonialism and its religious offspring are not abstractions. They live in bodies and intergenerational memory like inheritance. But wounds are not the end of the story. Ka Phan Nonglait’s name is now etched into the land she defended. Ophelia continues to create, to laugh that booming laugh, and demand bigger spaces for her incredible spirit. They remind us that healing is possible, that resistance is generative, that memory is a form of power.

Now again, I find myself wandering the memory lanes of the fern nursery at the botanical garden. These stories demand revival like those ancient species fighting extinction. They ask us to tend them, to pass them on, to let them grow wild in the commons of our collective consciousness. They ask us to believe that even after the worst devastations, life returns. That obscurity of margins is often the place where truth and reclamation coexist. That we can learn every seed by its name, only if we can lend our ears to the language of emergence.

Berkana is a non-stripe based reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming my patron through Paypal.

Subaltern Studies : It is a critical approach to history, originating in South Asia, that focuses on the experiences, agency, and histories of marginalized groups ("subalterns") often ignored by traditional elite-focused or colonial narratives

The foundation of Khasi society is the kur (clan), where descent is traced from a common female ancestor known as Ka Ïawbei Tynrai ("the root ancestress").

Thank you for sharing these stories, Swarna. Your essay reminds me of a unit I studied at university on The Uses of the Past, which opened my young eyes. We were encouraged to notice what and who was erased, and why certain stories (people, events, themes) gain prominence… and who that story serves now. I do not underestimate your courage in sharing your words.

This is important work you're doing, does it extend beyond writing here?